To ensure that subcontractors, suppliers and laborers are paid on federal works projects of more than $100,000.00, the federal government requires that the prime contractor post a payment bond pursuant to the Miller Act, 41 U.S.C. 3131-3134. The Miller Act, in essence, supplants mechanic’s liens, which are not available on federal projects.

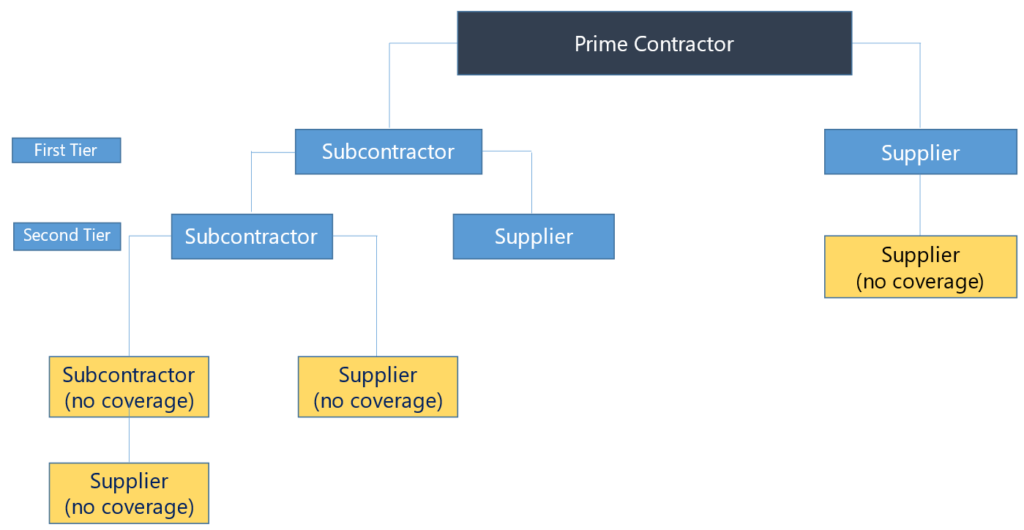

To qualify as a beneficiary of the Miller Act bond, the subcontractor, supplier and laborer (“Claimant”) must (i) contract expressly or impliedly with the prime contractor; (ii) contract directly with a subcontractor of the prime contractor, or (iii) supply labor or equipment to the prime contractor or the subcontractor in the prosecution of the work provided for in the contract. If a Claimant does not fit into these categories, then the Claimant is “remote” and has no bond rights. Below is a schematic demonstrating remoteness:

A Claimant proves its claim under the Miller Act by showing that: (i) the Claimant supplied material or labor in prosecution of the contract; (ii) payment has not been provided; (iii) there is a good faith belief that materials were intended for the contract work; and (iv) timely notice and filing requirements are met. United States ex rel. Hawaiian Rock Products Corporation v. A.E. Lopez Enterprises Ltd., 74 F 3d 972 (9th Cir. 1996).

Similar to a mechanic’s lien, there are certain notice requirements and time deadlines to perfect a bond claim. The Claimant not having a direct contractual relationship with the prime contractor must provide written notice of nonpayment to the prime contractor within 90 days from the date on which the Claimant provided the last of the labor or material for which the claim is being made. See, 40 U.S.C. section 3133(b)(2). This notice must state with substantial accuracy the amount claimed and the name of the party for whom the services were performed, or materials supplied. Notice must be sent by registered mail, postage prepaid, to the contractor at any place he maintains an office or conducts his business, or his residence. Service by someone authorized to serve a summons is also acceptable.

Suit to enforce bond rights are to be commenced after 90 days of last supplying labor or material and within one year after the day on which the last of the labor was performed or material was supplied. See, 40 U.S.C. section 3133(b)(1) and (4). This lawsuit must be brought in the name of the United States for the use of the Claimant bringing the action. The lawsuit must be filed in the United States District Court for any district in which the contract was to be performed and executed and not elsewhere, irrespective of the amount in controversy. Miller Act claims filed in state court will be dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction of the state court. Please note that the Ninth Circuit holds the one-year limitation is a claim processing rule and not jurisdictional. U.S. ex rel. Air Control Techs., Inc. v. Pre Con Indus., Inc., 720 F.3d 1174, 1178 (9th Cir. 2013) (“the Miller Act’s statute of limitations is a claim-processing rule, not a jurisdictional requirement.”). In other words, filing after the lapse of one year will not bar a Miller Act claim (at least in the Ninth Circuit, which includes Nevada).

The Miller Act is construed liberally in favor those supplying labor and materials to federal projects. See, Clifford F. MacEvoy Co. v. U.S. for Use & Benefit of Calvin Tomkins Co., 322 U.S. 102, 107 (1944). For that reason, federal law preempts and will not enforce certain standard contract provisions such as pay-when/if-paid clauses, delay claims, and others that are deemed to be in conflict with the Miller Act. See U.S. ex rel. Walton Technology, Inc. v. Weststar Engineering, Inc., 290 F.3d 1199, 1207 (9th Cir. 2002) (“Where subcontract terms effect [sic] the timing of recovery or the right of recovery under the Miller Act, enforcement of such terms to preclude Miller Act liability contradict the express terms of the Miller Act.”).

Please contact us with any questions or for further information.